Destination Net Zero by 2050

Introduction

In 2020, we wrote about the opportunity to accelerate and refocus efforts on net zero emissions as part of the post Covid-19 maxim to build back better. Since then, the Australian government has announced its plan to deliver net zero emissions by 2050, Glasgow has hosted COP26 and the IPCC has released its Sixth Assessment Report (AR6). The report was released in three parts, covering the physical science of climate change (2021), climate change impacts, adaptation and vulnerability (2022), and most recently, climate change mitigation (2022).

As of 2 November 2021, over 90% of the world’s emissions are covered by a net zero target, representing commitments from 140 countries (the Climate Action Tracker, CAT). This is a 20% increase on 2021 when there were commitments from 130 countries. Today, nine of Australia’s top ten two-way trading partners have net zero targets.

However, ratings by CAT show many of the commitments from Australia’s trading partners are critically or highly insufficient for meeting the Paris Agreement’s aim of “holding warming well below 2°C and pursuing efforts to limit warming to 1.5°C”. Of Australia’s top trading partners, the front-runners are the United Kingdom, rated almost sufficient, and Japan and the United States rated insufficient. Australia and New Zealand are both rated highly insufficient.

Nonetheless, Australia has the skills and technology to transition to low carbon technologies and sustainable business practices that enhance our environment and build a healthy society. Opportunities for renewable energy, better buildings, manufacturing & mining, transport, resource recovery, land use, education training & research and zero carbon communities were showcased by Beyond Zero Emissions (BZE) back in June 2020 through The Million Jobs Plan, and ongoing research into repowering manufacturing in The Hunter and Gladstone. The challenge here is to ensure that the increasing demand for resources (such as mineral resources) meets the rising environmental, social and governance (ESG) expectations of stakeholders.

So, how are we travelling?

Every element of society has a role to play. However, for governments, indications are there is a gap between promises and action and that current trajectories lie above the Paris Agreement’s long-term temperature goal.

At the corporate or business level, understanding and using greenhouse gas accounting and (financial/non-financial) carbon disclosures is essential for contributing to climate change mitigation and a sustainable future. This article outlines the major drivers for climate action, which leave no doubt that significant greenhouse gas emission reductions (and therefore the development of inventories) are critical to arriving at net zero.

Has Australia’s commitment to reducing GHG emissions improved?

Australia’s commitment, as indicated by its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) hasn’t changed since 2015. NDCs are the building blocks of the Paris Agreement and are intended to be reviewed and strengthened every five years. In this way, the NDCs should reflect the latest scientific knowledge, such as reported by the IPCC in its Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) 2021/22:

“Projected global GHG emissions from NDCs announced prior to COP26 would make it likely that warming will exceed 1.5°C and also make it harder after 2030 to limit warming to below 2°C”.

Furthermore, in the scenarios assessed by the IPCC, “limiting warming to around 1.5°C requires global greenhouse gas emissions to peak before 2025 at the latest, and be reduced by 43% by 2030; at the same time, methane would also need to be reduced by a third. Even if we do this, it is almost inevitable that we will temporarily exceed this temperature threshold but could return to below it by the end of the century” (United Nations Climate Change, 2022).

Australia’s NDC timeline is provided here and summarised below:

2015 NDC: committed to reduce emissions by 26 to 28% below 2005 levels by 2030

2020 NDC update: affirmed the 2030 target, outlined Australia’s technology-led approach to emission reductions

2021 NDC update: committed to net zero emissions by 2050, inscribed low emissions technology stretch goals, affirmed the 2030 target, and reported 2021 projections results

Australia will submit its second NDC to the UNFCCC (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change) in 2025.

States and Territories in the driver's seat

Australian States and Territories are leading the way in setting net zero emissions goals and shorter-term targets alongside renewable energy targets. The ACT, Victoria and Tasmania have legislated either net zero emissions or reduction targets or a combination of both. The ACT has achieved its first emissions reduction target of 40% by 2020, having met its target of 100% renewable electricity and keeping them on track to net zero by 2045. South Australia was the first to legislate targets to reduce greenhouse gas emissions under the Climate Change and Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reduction Act 2007, but has since set more ambitious targets.

Tasmania is also set to be nation-leading based on its draft Bill to amend the Climate Change (State Action) Act 2008 in response to the recommendations of the latest independent review of the Act (see the Tasmanian Government Response, 2021).This includes the recommendation to legislate net emissions (gross emissions less any carbon removals) are not to exceed net zero beyond 31 December 2030 (Tasmania achieved their 100% renewable energy target on 27 November 2020) and is now aiming for 200%. Switching to renewable energy is the keystone.

A summary of goals and targets across Australian States and Territories is provided below:

ACT: net zero emissions by 2045 and an interim 2020 reduction target (from 1990) legislated under the Climate Change and Greenhouse Reduction Act 2010. The ACT has also set interim targets beyond 2020 (e.g., 65 to 75% reduction of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2030)

NSW: net zero emissions by 2050, with a 50% cut in emissions by 2030 compared to 2005

NT: net zero emissions by 2050

QLD: net zero emissions by 2050, with the interim target for at least a 30% reduction in emissions on 2005 levels by 2030

SA: net zero emissions by 2050, with reduction in emissions by more than 50% below 2005 levels by 2030

TAS: net zero emissions by 2050. Under the Climate Change (State Action) Act 2008, Tasmania has a legislated target of reducing greenhouse gas emissions to 60% below 1990 levels by 2050

VIC: net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 (Victoria’s Climate Change Act 2017). The Act also requires 5-yearly interim emissions reduction targets to be set. The interim target for 2026–2030 is for emissions to reduce 45–50% below 2005 levels by the end of 2030

WA: net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

The imperative to measure GHG emissions continues

The IPCC’s AR6 reports (2021/22) consolidate the scientific body of knowledge about greenhouse gas emissions, the likely impacts of human-induced global warming and climate change, and mitigation strategies. Based on this information, countries must increase their NDCs (if party to the Paris Agreement) or ambitions to at least 43% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions (including a 33% reduction in methane emissions) by 2030 - if we are to limit average global warming such that people and the planet are sustained, by today’s living standards or better.

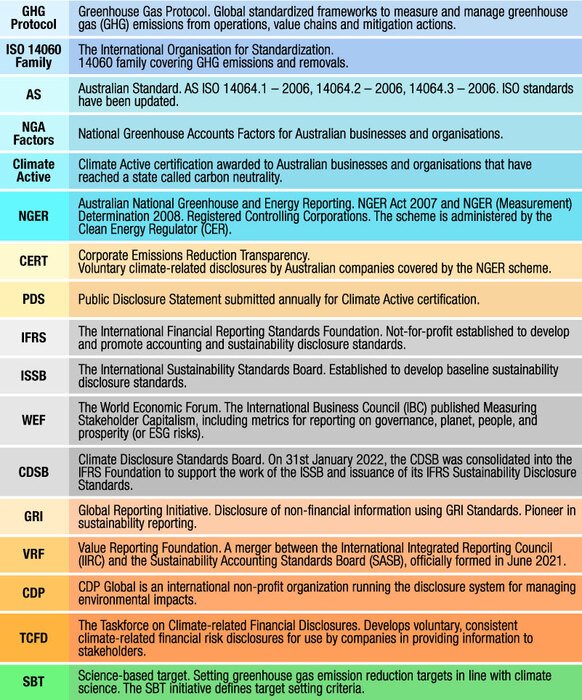

There are compelling reasons for state and non-state (e.g., companies, cities, regions, and financial institutions) actors to calculate and understand their GHG emissions. Given that Australia’s emissions reporting focuses on corporate emissions, including by industry sector, companies have a large role to play. In some cases, these requirements are mandated, while in other cases, stakeholder pressures have driven voluntary assessment and disclosure of climate change risks – either as part of sustainability reporting, assessment of environmental, social or governance (ESG) risks or within financial statements. Standardised greenhouse gas accounting is central to these initiatives - see figure GHG accounting and disclosures.

As we wrote in 2020, and updated here, GHG inventory and measurement is necessary to:

arrive at net zero emissions and meet interim GHG reduction targets

comply with applicable legislative requirements and mandated reporting, such as for climate-related financial disclosures

assure business practices by using Australian and international standards or globally recognised GHG accounting and disclosure protocols

embed climate change action in operations, the value chain and sustainability reporting

meet the rising expectations of stakeholders.

The obligations for businesses in Australia are underlined by the Memorandums of Opinion by Mr Noel Hutley SC and Mr Sebastian Hartford Davis, and published by the Centre for Policy Development (CPD) on “Climate Change and Director’s Duties” in 2016, 2019 and 2021. In 2019, their opinion stated, “There are, at the present time, significant and well-publicised risks associated with climate change and global warming that would be regarded by a Court as foreseeable”.

The NGER Act 2007

Mandated registration of, and reporting by, controlling corporations that meet thresholds for GHG emissions and energy production or consumption is legislated under the National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting Act 2007 (the NGER Act 2007). This Act is administered by the Clean Energy Regulator based on the thresholds described below.

Facility threshold:

25 kt or more of greenhouse gases (CO2-e) (scope 1 and scope 2 emissions)

production or consumption of 100 TJ or more of energy.

Corporate group threshold:

50 kt or more of greenhouse gases (CO2-e) (scope 1 and scope 2 emissions)

production or consumption of 200 TJ or more of energy.

A Scope 1 emission of greenhouse gas means the release of GHG into the atmosphere as a direct result of an activity or series of activities (including ancillary activities) that constitute the facility. A Scope 2 emission of GHG means the release of greenhouse gas into the atmosphere as a direct result of one or more activities that generate electricity, heating, cooling, or steam that is consumed by the facility but that do not form part of the facility.

In February each year, the Clean Energy Regulator (CER) publishes the NGER datasets for the previous financial year, the most recent being the Corporate Emissions and Energy Data for 2020-21. In addition, the CER publishes data highlights, which show key points of interest including reported emissions by industry and electricity sector emissions.

Corporate Emissions Reduction Transparency (CERT) Report

The Corporate Emissions Reduction Transparency (CERT) report supports climate-related disclosures by Australian companies covered by the NGER scheme (CER, 2022). Participation is voluntary for all companies reporting more than 50 kt of emissions per year under the NGER scheme. It is intended to give investors, shareholders and the public transparency of actions taken by companies to reduce net emissions.

However, as for the NGER scheme, this is limited to Scope 1 and/or Scope 2 emissions as Scope 3 emissions are not reported. According to the CER, Scope 3 emissions are indirect GHG emissions other than Scope 2 that are generated in the wider community and occur from because of the activities of a facility, but from sources not owned or controlled by that facility’s business.

Climate Active

The Climate Active Program is the Australian Government’s endorsed carbon neutral certification, which is underpinned by Climate Active Carbon Neutral Standards. To achieve certification, an entity (such as an organisation) must – measure emissions, reduce as much as possible, offset remaining emissions, then publicly report on its achievement. Certification allows businesses and organisations use of the Climate Active trademark, helping consumers and the community to immediately identify products and services that are carbon neutral.

Greenhouse gas accounting and reporting

Australia needs to meet its international reporting obligations and NDCs under the Paris Agreement. The primary framework enacted in Australia for reporting and disseminating company information about greenhouse gas emissions, energy production and energy consumption is the NGER scheme as discussed above.

Standards have been developed to ensure consistency of GHG accounting and reporting practices. These standards may be mandated (such as the National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting (Measurement) Determination 2008) or voluntary such as the AS ISO 14064 series on Greenhouse Gases and the Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Protocol, which was introduced in 2001 (see figure GHG accounting and disclosures).

The GHG Protocol established a common language and is the default methodology underlying most ESG disclosure standards. It provides standards, guidance, tools and training for business and government to measure and manage emissions. This protocol established a common language and is the default methodology underlying most ESG disclosure standards.

The problem of Scope 3 emissions

Most organisations pick and choose which, if any, Scope 3 emissions they will include in their inventory because they are outside their direct control (e.g., embodied emissions in materials purchased) and therefore more difficult to track and calculate.

Corrs Chambers Westgarth (October 2021) however, observe that the increase in net zero commitments (including by Australian national and state/territory governments) brings with it increased scrutiny of Scope 3 emissions - particularly amid the recognition that these can make up a significant proportion of a company’s GHG account. Companies that exclude Scope 3 emissions risk allegations of greenwashing when reporting on progress towards net zero emissions targets.

In April 2021, Mr Noel Hutley SC and Mr Sebastian Hartford Davis, via the Centre for Policy Development (CPD) also provided opinion on the litigation risks associated with greenwashing in the context of net zero commitments. The legal opinion states that “a company (and its directors) could be found to have engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct” by not having had “reasonable grounds to support the claims contained within its net zero commitment”.

An article in the Harvard Business Review (December 2021) attributes the lack of Scope 3 emissions reporting to conceptual problems arising from the GHG Protocol – the same emissions are reported multiple times by different companies, while some entities ignore emissions from their supply and distribution chains (i.e., Scope 3 emissions). To address this, the authors propose a new system for accounting for climate change (an E-liability accounting system) to track emissions across the entire value chain.

All indications are that expectations for disclosure of Scope 3 emissions are increasing. The Australian Financial Review recently reported (March 2022) on the urging of Australian regulators to follow their United States counterparts by enforcing greater disclosure of corporate GHG emissions, including Scope 3. This is in response to the US Securities Exchange Commission’s (SEC) draft rules to enhance and standardise the disclosure of climate risks. These draft rules will require US registered companies to report the Scope 3 emissions of their customers if they are material to that company’s business.

Sustainability and ESG disclosures (or reporting)

Disclosure and transparency are the underlying principles of standardised accounting and reporting frameworks for building stakeholder trust and achieving environmental, social and governance (ESG) goals. Calculating and reporting on carbon/GHG emissions and management is a critical part of the ESG. Organisations may choose to include this information in sustainability reports and/or report through one of the voluntary carbon focused schemes available (such as the CDP global disclosure system).

Such initiatives provide transparency for stakeholders such as:

investors – to manage risk exposure (e.g., risk of stranded assets), track progress on decarbonisation, and understand and apply ESG ratings

policy and law makers – to maintain a level playing field and avoid unintended consequences, to set GHG reduction targets and ensure controlled and fair transition to a low carbon economy

consumers – to drive innovation for low carbon design and meet increasing demand for sustainable products

manufacturers – to meet increasing demand for visibility about embodied carbon (e.g., carbon labelling) in the products and services they procure.

The figure GHG accounting and disclosures summarises the key global and Australian approaches, noting the recent formation of the International Financial Reporting Standards Foundation (IFRS) and the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) (announced by the IFRS in November 2021) to deliver a global baseline of sustainability-related disclosure standards. Through these initiatives, we can see the converging of non-financial (e.g., the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) and CDP) and financial sustainability reporting (e.g., the Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures, TCFD).

In addition, the World Economic Forum (WEF) has developed a set of ESG metrics that bring together work from the leading sustainability standards and frameworks, such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), SASB (now part of the Value Reporting Foundation), GHG Protocol, TCFD and Science-based Targets initiative (SBTi).

The TCFD is a living document that produces recommendations to develop voluntary consistent risk disclosures for use by companies to inform investors, lenders, insurers, and other stakeholders. The Task Force considers the physical, liability and transition risks associated with climate change and the recommendations help an organisation to think about climate risk and its possible impact on the way they do business. Science-based targets show organisations how much and how quickly they need to reduce their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to meet global goals for climate mitigation. The SBTi has also recently released (April 2022) its new Foundations Paper on Net-Zero for Financial Institutions, which assists the sector to transform net zero commitments into robust targets and actions.

At the National level, the NGER scheme publishes data, and data highlight reports, on an annual basis. Similarly, the Australian Climate Active initiative publishes the Public Disclosure Statements (PDS) of its certified organisations.

Given the range of mandatory and voluntary reporting schemes, it is important at the outset, to determine what type of data is to be collected and how it is to be managed to satisfy all reporting requirements and avoid duplication of effort or extensive re-purposing.

Acceleration to 2030

Developing an emissions inventory now, if not done already, and implementing greenhouse gas accounting is essential to Australia reaching its short-term emissions reductions targets by 2030, if we are to constrain global warming and mitigate the resulting climate change impacts. This will also prepare organisations for increasing expectations about climate-related financial disclosures and potential mandates such as implemented in New Zealand (for large publicly listed companies, insurers, banks, non-bank deposit takers and investment managers) and through the Singapore Exchange (for issuers).

GHG emissions and climate risks are material issues for most companies, and evaluation should be undertaken of both the risks to the organisation and the impacts of the organisation’s activities on people, planet, prosperity, and governance. This includes analysis of emissions throughout the value chain covering all emission scopes and associated complexities for calculating Scope 1 emissions, in some sectors (although within the organisation’s control), as well as Scope 3 (outside of its direct control).

However, organisations also need to be responsive to:

The state of scientific knowledge of human-induced climate-change impacts and scenario analysis

Global harmonisation of reporting standards and metrics, such that sustainability/ESG performance (including GHG emissions reduction) is comparable and consistent

Increasing stakeholder expectations for increased value creation because of innovative and responsible practices.

Investors and stakeholders now expect companies to report on non-financial issues, risks and opportunities with the same discipline and rigour as financial information.

Conclusion

The world is coming together to accelerate efforts of 43% GHG emissions reduction by 2030 (which still results in an overshoot of 1.5°C) and net zero by 2050, or earlier. Every organisation also needs to commit to shorter-term state, and national targets and goals for Australia to achieve its global commitment. Business should engage with the review and strengthening of Australia's NDC at five-year intervals, if not to at least ensure it is aligned with export markets that require evidence of low-emissions credentials.

Covid-19 magnified the importance of companies operationalising sustainability goals in its activities and processes to increase value creation, meet rising stakeholder expectations, and minimise its environmental and social impact. The development of a global baseline of sustainability related disclosure standards and universal, industry-agnostic, ESG metrics (mainly quantitative) will showcase these gains and provide for comparable and consistent evaluation of GHG reduction and overall ESG performance.

Access to renewable energy is key for many industrial activities, but several states have already achieved 100% renewables targets, and work being undertaken by Beyond Zero Emissions in Queensland and NSW indicates this is a real opportunity.

Implementing GHG Emissions Reporting in Your Organisation

Shelley Anderson is a freelance Certified Environment Practitioner and sustainability professional with experience in Australia and the UK. Her expertise includes environmental risk assessment and management, due diligence, and reporting across a broad range of industry sectors. Shelley was also a Director of the Cotswold Canals Trust (UK) where she led the Natural Environment team and applied her skills to charity governance and impact.

Written in consultation with Jenni Mulligan, Co-Founder and a Principal Consultant @ iSystain .

Contact us to organise a chat with an iSystain Consultant or a demo of iSystain’s Sustainability and Emissions Reporting solution.